What is the Future of Canadian Manufacturing? The Agenda

TVO Today

Apr 10, 2025

Steve Paikin: Canada’s manufacturing sector faced challenges even before President Donald Trump imposed tariffs on goods made here. The overall sector has shrunk both in its contribution to our economy and the number of workers it employs. So how should Canada support existing companies and their workers as tariffs take hold, and what’s the way forward to building up a homegrown manufacturing sector that provides higher skilled jobs and in demand goods?

Let’s get into that with in Vancouver, British Columbia, Jim Stanford, economist and director at the Center for Future Work in Cambridge, Ontario. Michelle Ian, vice President of Research and Innovation at Conestoga College, and a member of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

And here in our studio, Jason Meyers, CEO, at NE. That’s next generation manufacturing Canada. And Brendan Sweeney, managing director at the Trillium Network for Advanced Manufacturing. And it’s good to have you two gentlemen here in our studio and to our friends in points beyond Jim and Michelle. Thanks for joining us tonight on TVO.

Wanna bring up a chart just to, uh, inform our discussion here. This is manufacturing employment in Canada since the late 1990s. Back then, manufacturing was a bit more than 15%. Of Canada’s total workforce, and for those listening on podcast, we’re looking at a ski hill here. The numbers just go down, down and down.

By 2019, it had gone from more than 15% to roughly 9%. I. Where it sort of remains today. So let’s start with the whys behind that. Jim Stanford. Why did we lose all those jobs?

Jim Stanford: Well, the steepest part of that ski hill that you just showed, uh, Steve, is the period of the early two thousands when, uh, manufacturing was really hammered by a number of factors, uh, including, uh, a very, very high Canadian dollar.

So for a while, uh, 2006, 2007, the Canadian dollar was trading for more than an American dollar. Which doesn’t make any sense given the relative level of costs and prices in the two countries, uh, partly because of the big oil boom that was happening out west at that time. That was during the maximum period of construction of oil sands, uh, facilities and so on.

So that was the worst of it. Uh, since then, we have kind of stabilized and I think we should see that as a victory. Uh, frankly, the fact that. Manufacturing employment has stayed fairly steady as a share of total employment. And, and that’s in a labor market that’s been growing quickly. So we actually have added in, in terms of numbers of jobs, we have added some, some jobs in there.

So, um, I, I do think that, uh, you know, Trump aside for the moment, uh, Canada’s done a pretty good job of maintaining manufacturing as a core part of our economy.

Steve Paikin: Well, let me ask Michelle to follow up by characterizing the kinds of jobs that have been lost over the last two and a half to three decades.

Michelle Chretien: Yeah, that’s interesting. Um, I think that the kinds of jobs actually span, um, a variety of different, uh, different skill domains. And one of the things that certainly we hear in talking to manufacturers on a daily basis is they’re seeking. Both skilled laborers and general laborers. Um, but the skilled labor is becoming more and more difficult to find due to, um, perceptions of work in the manufacturing industry.

Certainly other opportunities that are available to skilled workers and, um, a lack of young people pursuing, uh, careers in the skilled trades. Um, and then in the general labor category, I think there’s just really tough competition and salaries have a hard time keeping pace in a way that. Keeps Canadian manufacturing competitive from a price point perspective.

Steve Paikin: Alright, with that background in place, Jason, lemme bring you in now and I’m not only gonna ask you to put on the hat that you’re currently wearing, but you’re the former head of the Canadian manufacturers and exporters as well. So you know this file all too well. Tariffs are taking hold. What are the best ways available do you think, to support manufacturers and workers?

Given the new realities we’re dealing with,

Jayson Myers: well, let’s keep our fingers crossed. The tariff issue is just a short term issue and, uh, and is not gonna be sustainable, uh, over the long term. Assuming that, uh, the first thing we need to do is help companies stabilize employment. One of the reasons why, uh, Canadian productivity over that period that Jim was talking about from 2000, 2010, one of the reasons why we didn’t do too well in, in, uh, productivity is we kept, we kept a lot of workers.

Employed, although we lost workers. And, and one of the, one of the other factors here, remember, is the, the opening up of the North American market to Chinese imports too during that period of time. So we, I, I think right now we face a, a real problem, of course with, uh, with the tariffs. It’s giving companies a great opportunity to look for new markets, look for new customers, look for new suppliers, new technology partners as well.

This is the time to. Invest in, in new technology, in innovation, in new markets. The problem is that with all the uncertainty, everybody’s very, very cautious right now about their cash and companies will need to invest their cash or that’s where they look to invest. But they’re probably gonna sit on it for now.

They’re gonna sit on it for now. So hopefully after this, uh, this disruption passes where we’ve got a little bit more clarity. Then the question is, where do manufacturers go from there? And as you were saying, Steve. The sector was facing some major problems in terms of competitiveness, aging, workforce, and, and huge competition from, uh, from around the world, even before, uh, the, the tariff issue.

So I think in the long term, let’s focus on that.

Steve Paikin: Hmm. Let’s put the microscope on one sector, autos, autos and trucks, cars, whatever you want to call it. How automated is all of that right now compared to, say, when we had 15%. So people working in the manufacturing sector two and a half decades ago,

Brendan Sweeney: uh, in certain assembly plants in Canada, in certain vehicle assembly plants in Canada.

The updates, the investments in automation in, you know, uh, facilities that were already dictated by an assembly line, uh, are just incredible. And in the, you know, the bigger Toyota plants that, you know, manufacture about nearly 40% of all the vehicles made in Canada today. Uh, there is AI machine vision. All these fun technologies are right there on the shop floor, and this is what, you know, the, the production staff is engaging with.

I don’t know if those technologies have been rolled out consistently across every single assembly plant. So there’s possibilities. There’s a lot, uh, that can be done. How much has been done? That’s a question. And then it’s very, there’s a real diversity of technological, of automation approaches. But I’m wondering, is that in the automotive parts industry,

Steve Paikin: is, is that part of the explanation behind why there are many fewer manufacturing jobs in Canada today?

Mm-hmm. We’ve automated a lot more.

Brendan Sweeney: Uh, we, we have, but at the same time, if you look at the, the, you know, the companies that are making vehicles and making auto parts in Canada, they still. Employ a lot of people. So there would be other sectors, steel, chemical, paper where output has, uh, grown and employment has decreased.

But in automotive, it has, uh, stayed relatively consistent. There have been gains, but those gains have led to other types of jobs, uh, within, within the sector.

Steve Paikin: I gotta ask the former economist for the Canadian Auto Workers Union, whether or not he. Um, opposes or understands or embraces the notion of more automation in the auto sector.

Go ahead, Jim.

Jim Stanford: Oh, uh, Steve, I think it’s quite wrong to blame automation for what’s happened, uh, in the decline of jobs. Um, uh, all of the modern assembly plants in Canada use a, a huge amount of robots in automation. And this is a good thing. I would much rather have a plant that, uh, is automated and hires 3000 people rather than one that uses the old technology and hires 4,000.

Uh, the reason being the one with old technology isn’t gonna stay open. Uh, the key reason why automotive employment has declined from that peak in the late nineties. Just that we’re making a lot less cars. Uh, in 1999 we made 3 million, uh, assembled vehicles in Canada. That’s about twice as many as were sold in Canada and Canada ranked as the fourth largest, uh, automotive assembler in the world.

Uh, last year we made half that and yet we bought 2 million, uh, vehicles in Canada. So we’re now producing much less than we buy in Canada. That’s the main reason. So automation and innovation and new tech is gonna happen and it has to happen, and it is one of the reasons why manufacturing, employment. As a share of the total is shrinking everywhere in the world.

Mm-hmm. Uh, and I think, uh, certainly, uh, an enlightened, intelligent union like unifor. It’s not gonna stand in the way of, uh, using the latest technology in our plants. Uh, what the union really wants is to make sure those plants are in Canada. And, uh, given what Trump has done, uh, it’s gonna be more important than ever.

The, the federal government, the provincial government, all the companies are laser focused on keeping that footprint here in Canada.

Steve Paikin: Well, let me follow up with Michelle on that, because of all of the uncertainty that we’ve been talking about. Now that these tariffs are coming on, do you think manufacturers are going to be, say, more reluctant?

To invest in the innovation and the automation that clearly is part of the future.

Michelle Chretien: Yeah, I think short term, you know, as, as Jay was saying, the unfortunate consequence is that people are going to hold back on, on investment and we’re already, we’re already seeing that. Um, I do wanna jump in on the, on the question of, of the adoption of technology and what that means for employment.

I think there are lots of examples in other jurisdictions around the world where embracing robotics and automation manufacturing has actually resulted in a net. Um, net and all or net increase in jobs across the, across the economy. So I think it isn’t something to be scared of. In fact, unions and, and governments and companies partner together in, in company, in countries, in Europe, um, to embrace and encourage the adoption of automation.

I think our real challenge in Canada is that we’re not doing enough of it. Um, we talk a lot about Canadian productivity and, and our gap or lagging productivity compared to, to other countries around the world, and I think part of that is a lack of adoption of technology. So we talked to about, about automotive.

Certainly another big manufacturing sector in Ontario is the food and beverage sector who are embracing automation at about the same rate as the, as the, uh, automotive industry, but it’s still relatively low compared to other countries around the world. So think Canada. Was last ranked 15th of 20 company countries when it comes to, uh, to the adoption of robotics technologies.

Um, and that was actually moving down since 2019. So I think that’s an area that, that we need to look at. And nothing like a good crisis to, to. Give us the opportunity to focus, uh, inwards and think about what we might want to do when the, when the current season of tariffs, et cetera, has hopefully passed.

Um, so yeah, to answer your question, short term, I think people are gonna hold back on investing, but I really think that governments in particular should be looking at how we encourage that investment now and, uh, and in the future.

Steve Paikin: Jason, I should get you to weigh in on what role you think automation and AI have played in that ski hill graph that we saw earlier.

Well,

Jayson Myers: one of the things I think we have taken into consideration is that the automotive or the automotive and the manufacturing value chain in Canada, uh, is a lot bigger than what that graph shows. All of the technology, all of the engineering services, all of the business and financial services that go into manufacturing that footprint.

Is much larger, probably over twice as si twice the size of, of, uh, the, uh, the employment in manufacturing itself. So I think that’s very important. But, but now, especially with ai, uh, and all of these other technologies that are, are coming into play, you know, automation’s important. We have disproportionately more small companies in Canada’s, uh, manufacturing sector, more small companies.

Proportionately than, uh, than the US does. So we have to understand the sector. We have to understand that Canadian manufacturers, by and large, create value through much more customized product. They’re focused on value, they’re not focused on volume way we measure manufacturing is, you know, outdated. It’s 40 years old.

It’s based on, on manufacturers producing stuff. Well, today, the, the nature of the business is about producing solutions and that, that. Means it’s manufacturing, but it’s also technology and it’s also services. And so let’s, let’s take a look at that and how, how ai, how some of these new technologies fit into that.

Steve Paikin: So we’re about creating solutions as opposed to products. Should we not obsess so much about these numbers we’re looking at? I, I think we need to

Jayson Myers: look at them in the context of, of modern. Manufacturing economy where, uh, where the footprint is much greater than these numbers alone. We need to, we need to produce products.

Uh, there, but today because of some of the, uh, the advances in ai, for example, every product, every machine, every process is a data platform. And today, you can read the data, the services that you’re providing from that, uh, uh, from all of that, uh, that digital technology, that’s a source of, of value for, for companies.

Improving product, improving, uh, their own processes, improving delivery times, improving the quality of the product. There’s a company here in Ontario called Shim Co. And they manufacture the most basic product you could ever think of, a metal shim. And this is what you put in to, in between, uh, um, parts to stop them vibrating.

But they put a sensor in that shim and their business is not. Making the shim, their business is reading the outcome of the sensor, the the vibration, and. They’re, they’re a service company, uh, that’s doing a lot of business with the aerospace industry. Uh, right now, because of all of the products, you want to measure the vibration in a, in an airplane.

So, you know, we need to think differently about what, how manufacturing services and technology all work together. AI, for instance, is allowing companies to figure out where they have problems in their processes, where they can add value to their products. And I think we’re at, at really the cusp of a, of.

A real unique revolution in manufacturing where if companies can jump onto this, they can continue to drive, uh, uh, what is has been fundamental to Canadian manufacturers and that’s producing value for customers. It’s not getting product out the door.

Steve Paikin: Well, okay, lemme do an example here with Brendan because, uh, you know, I, I have seen numerous announcements by the Prime Minister of Canada and the premier, the previous Prime Minister and the current premier of Ontario and his economic development minister.

Opening up new facilities for EV manufacturing here in the province of Ontario. Given the regimen that we’re going through right now, tariffs and all of the nonsense from south of the border, uh, do you think we are in the midst, potentially of an existential crisis as it relates to all of that in investment in EV manufacturing in Ontario that we have committed to?

Brendan Sweeney: Probably not. Uh, you say

Steve Paikin: probably

Brendan Sweeney: not. Probably not, because I can’t, I don’t have a crystal ball. The, he’s an economist. Yeah. The, um, the trajectory of the world is going electric. There may be a blip in North America. Uh, but from everything we understand in the 2030s and the 2040s and the 2050s, the mix of vehicles.

We’ll have more electric vehicles. Will we hit one? I get that’s not the

Steve Paikin: existential crisis I’m thinking of though. I’m thinking of tariffs, repatriating all of what we’ve got here to the United States, which is what Trump wants. I don’t think the United States could handle it

Brendan Sweeney: all. Uh, I, I, I don’t think they have the workforce.

Uh, I think that companies chose to locate these facilities in Ontario for a good reason and not the United States and not Tulsa, Oklahoma. For a similarly good reason. Uh, part of that is talent. Uh, part of that is we have a mature ecosystem. Mm-hmm. I mean, the, the, the manufacturing ecosystem in the GTHA extended out to Waterloo is just absolutely incredible.

It’s one of only two major metropolitan areas in North America that has full scale aircraft and full scale automotive assembly. Dallas-Fort Worth is the other one. It’s the only one that. Adds to that integrated steel making the ability to make nuclear reactors biopharma. And we’re forgetting one of the largest, if not the largest segment of manufacturing in, in the area.

And that’s food. So all of that provides hard to measure, but just incredible value to anyone who’s locating in Simco County or in St. Thomas. Okay, I get you. And is it ex. Our automotive industry has been in a bit of an existential crisis since the 1960s. Yes. And we always kind of come out on the other side of it, so I think we’ll come out somewhere good.

It might be a little bit different. It might be a little bit more delayed than what we had anticipated a couple years ago when we were talking about on this show. Mm-hmm. Um, but will we be making batteries for vehicles in 2030 at three or more facilities in Canada? Most likely you Bel,

Steve Paikin: what did you say?

Brendan Sweeney: Most likely. Most likely. I

Steve Paikin: don’t have that crystal. I still want a yes, but Okay. Most likely, I guess we’ll have to take right now. Hey. Hey Steve.

Jayson Myers: Could I, could I add in here too? Sure. Last week, in the midst of all this chaos, Siemens made an announcement they were investing $150 million in the establishment of a global in EV battery.

Uh, research hub here in, in Southern Ontario. Mm-hmm. That they wouldn’t do that if they weren’t serious and if they weren’t taking advantage of, as Brendan says, of the skills of the, uh, of the great, uh, innovation ecosystem that we have in this province.

Steve Paikin: No, fair enough. But, okay. I’m gonna get Jim Stanford back in here now, because of course it didn’t take too long once Trump threatened his tariffs for the auto manufacturers in the province of Ontario to start laying people off.

Understandably, if there’s. If there’s not gonna be, um, anyway, you know where I’m going with this. What’s happening with employment insurance right now, Jim? Um, what needs to change to take, uh, account of the new reality we’re dealing with?

Jim Stanford: Okay, Steve, I will answer that question, but I’ve gotta jump in on the ev uh, discussion you were just having as well.

Uh, because I, I share Brendan and Jason’s confidence that we’ve got the amazing makings of, uh, a world leading EV industry. And the world is going to EVs, no doubt about it, but the industry is gonna need some forceful and targeted help to get through the next, uh, two to three to four years, however long this takes.

’cause in addition to Trump’s tariffs, he has also pulled the plug to use an analogy. Uh, on the whole, uh, Joe Biden, uh, program to accelerate EV development in the us. You know, Trump was on TV yesterday holding up lumps of coal saying we’re gonna support the coal industry, uh, instead of, uh, trying to move forward and position America at the, for forefront of that EV revolution.

So, Canada’s very well positioned long term, but, uh, we are gonna need some very focused assistance, and that includes, uh, focused assistance for the workers. So, I, I will answer your question now. Um, EI is still full of holes. Uh, we knew it was full of holes when the pandemic hit a few years ago. That’s why the government had to move to the Serb, uh, vision of emergency payments directly to workers and so on.

There was a promise to fix EI and make sure that more unemployed people could qualify for the benefits and it hasn’t been fulfilled. So, uh, we are in a situation where we’re seeing, you know, temporary layoffs that to plants that are idled, waiting to see what happens with the tariffs, but potentially longer term layoffs, uh, if we get closures or restructurings happening.

Uh, so we’re gonna need a, I think a whole slate of improvements in ei uh, eliminating the waiting period. The government to its credit has done that increasing, uh, the level of benefits. A key thing we should fix is, uh, how EI is integrated with training. I. Uh, right now, if you go into vocational college or back to university or something, you would lose your EI benefits.

Uh, and that doesn’t make sense. We want people to adjust and learn new skills, so we’ve gotta fix that problem where people aren’t financially penalized for taking the leap, uh, back in. So, EI is gonna be a vital, uh, vital tool, uh, in the, in the next year or two as we go through this and we’ve gotta fix it.

Steve Paikin: Michelle, we’ve been talking a lot of auto sector here so far, but I guess I should ask, what else are we really good at making in this province?

Michelle Chretien: Oh, that’s a good question. So we, and we do tend to talk about auto a lot when we’re talking about manufacturing, but I, as I alluded to earlier, food and beverage is, is.

Of almost equal size. I think they out overtook, uh, automotive manufacturing slightly during the pandemic. But, um, an equally important, uh, sector, particularly in Ontario where we have the largest cluster of food and beverage processing in Canada. So that’s a really important one. Lots of jobs. Um, and lots of really great innovation and opportunity in that space.

I think, uh, we also, obviously there’s aerospace, which we would include in kind of transportation, um, and let’s not forget chemicals, rubbers, plastics, and also, um, biopharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical manufacturing. So I think there’s been an interesting storyline in Sarna over the last. Number of years with a shift to looking at biochemicals and biofuels.

Um, and I, I think that stands out as an example of what Ontarians and Canadians can do, um, when faced with a challenge, right? Is pivot, is look at where we add value. And as Jay was alluding to earlier, um, this idea of focusing not just on producing stuff and as much as much stuff as we can get out the door, but really looking for opportunities to add value, to leverage data, to embrace technology in order to.

Create something meaningful for, for a customer, not just a lot of things for, for a customer.

Steve Paikin: Can I just ask you two here, did you both go to this conference in Germany, this industrial conference in Hanover? We had, we were talking about it before we went on the air here. We had Okay. What, I mean, presumably you, you picked up some sense in the rooms that you were in about what kind of reputation we have.

As it relates to manufacturing in this country, what are you hearing? So, first of

Jayson Myers: all, Canada was a partner country, uh, and officially invited by Chancellor Schultz to participate. The reason was because the Germans. No, that Canada is a source of tremendous industrial technology, uh, here everything from robotics to ai, of course, to quantum to advanced materials.

That’s why we were invited. Uh, there, uh, there were a thousand Canadians in Hanover last week. They were looking for new customers, new suppliers, new innovation partners, new investors, and, and I think that’s exactly, uh, the type of. The type of reaction, everybody was very positive. Uh, when you had Chancellor Schultz get up and said, we believe in Canada.

Uh, he got a standing ovation, mainly from the Canadians, of course, uh, there. But it’s so important and, and to see Canada as a reliable trading partner, but also a reliable supplier and a reliable customer for, for German. Businesses, uh, as well.

Steve Paikin: Well, Brendan, I don’t wanna be a killjoy here, but I’ll get you to react to another chart we’re gonna put up.

This one is gonna show the decline in value added manufacturing as a percent percentage of our economy here in Canada. Uh, and again, for those listening on podcast, I’m gonna describe the same ski hill again. It was once upon a time, uh, I, I guess as high as 17% in the late 1990s, but it’s around 9% today.

So how do Canadian manufacturers reverse that trend and increase? The sale of value added products.

Brendan Sweeney: Mm-hmm. I think that we really target and focus on higher value industries or industries with the potential to be high value. I think about space, I think about biopharma as two industries that are at once high, highly productive, high value, high tech, and that really fit.

The profile of the people that are graduating from Canadian universities and Canadian

Steve Paikin: colleges. People in Hamilton will want, and St. St. Marie will wanna know if steel is on your list as well.

Brendan Sweeney: Steel’s already there. Steel. Steel and, and we’re investing. And uh, and some of that steel might go to the, uh, go to the space industry.

Uh, so steel is on that list. Um, but biopharm more, biopharma more space. Uh, you know, the likelihood we will get another integrated steel mill in the next. A decade or two is low, but the likelihood that, um, we will invest at the Faco and at Al Goma, and that’s what I’m gonna call them, even though they’re called that anymore.

Steve Paikin: But no, I’m with you. Usually the old name. Yeah.

Brendan Sweeney: Um, well, we are investing there and the Arcelor Middle. The Faco mill that is that company’s flagship mill outside of. I guess Luxembourg outside of the eu and I think it will remain that way. Uh, that’s probably the best steel mill in North America. Okay.

Steve Paikin: Michelle, your post-secondary institution obviously is in the business of trying to prepare young people for the jobs of the next generation. And I guess I want to know what kind of skills as it relates to manufacturing, do you think, uh, they’re going to need to have as processes become more complex and sophisticated going forward?

Michelle Chretien: Yeah, so I think we see that there’s certainly continued demand for skilled trades workers. So across, um, you know, welding, machinists, uh, those types of, of roles are highly coveted and, and there’s still a gap in manufacturing industry today. But then I think we see more integration as we’ve all been talking about, of technology, um, whether.

Anything from robotics to ai and that requires a different skillset. And so, you know, we and others, all the post-secondaries in Ontario, and by the way, Ontario has an absolutely world class com completely outstanding post-secondary education system. And we are very blessed. And that is one of the core reasons why companies choose to invest here is because of the talent that we produce.

So I think we’ll see, um, across our STEM programming, so engineering, engineering technologists, um, those, uh, students, those graduates will be, I. We will be, I was gonna say looking, but it’s actually more of it the other way around. Companies will be looking to those graduates, um, to fill their, to fill their ranks.

And I think we have a challenge there a little bit in when we talk about the, the labor shortage and manufacturing. And there was a, um, Jim made a great point that I wanna come back to about the period that we’re in right now where we see layoffs. Um, and potentially workers having to access employment insurance benefits.

This is an amazing time to look at the long between 80 and 200,000, uh, vacancies in the manufacturing industry across Canada, depending on who you ask, what an amazing time to help those workers reskill or upskill to fill those vacancies. Um, so I think there’s Jim’s absolutely right. There’s a fix. That we could look at there.

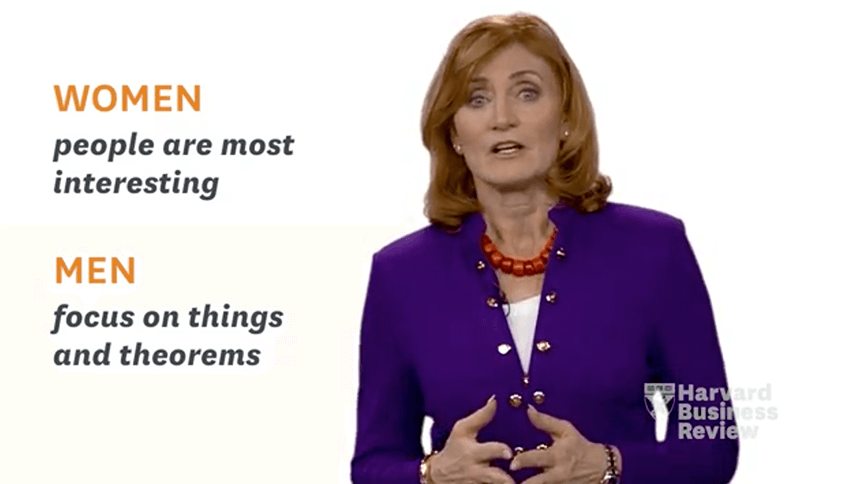

Um, excuse me. And I think that the, the industry, so we’re creating all these graduates. We have amazing people. We have ama an amazing education system. And the question then becomes, why aren’t those people choosing jobs in the manufacturing sector? I. And there, I think we have some work to do around the perception of jobs in manufacturing.

Um, and some work to do on the diversity end for, for, uh, to be honest. So we have women, for example, has 50% of the workforce and less than 30% of the manufacturing workforce. And that number has been flat for basically. Certainly since I’ve started talking about this, so a couple of decades. Um, so we have the talent, there’s no question.

I think there’s a bit of a matchmaking exercise that, uh, that all of us need to, to engage in. And there’s some great work going on. I just think we need to, uh, to stay the course and not underestimate how long it takes to change hearts and minds when it comes to, to perceptions of, of what jobs and manufacturing can be, because there’s no question that they are not what they might have been in the past.

Um, they are high tech, they’re exciting, they’re embracing the latest technologies. Um, and these are careers really, um, that young people should be, should be wanting to go into.

Steve Paikin: Well, Jim Stanford’s been coming on this program for a couple of decades, trumpeting what you just said, so I, I know he is, uh, you’re preaching to the choir with him.

But Jim, what I wanna ask you is if we wanted to create a national industrial strategy in this country and we wanted to support a kind of an advanced manufacturing sector going forward. Gimme some sense about what that looks like.

Jim Stanford: We have got such a toolbox of different policies and levers, uh, and regulations that we could apply, uh, in manufacturing.

And when we look around the world at countries that have been successful in this mission, uh, of using active industrial policy to support high value industries within their own jurisdictions, uh, we’ve got lots of experience to, to draw on, uh, you know, in Canada, our auto and aerospace. Space and, uh, pharmaceutical industries here are the result of active policy, active national strategies to bring those industries here in auto.

It started with the auto pac, of course, uh, with aerospace. We had everything from public ownership of aerospace manufacturing to, uh, proactive procurement strategies to make sure that we bought. Canadian made aircraft for our airlines and our military, uh, in pharmaceuticals. It was all tied in a sort of a quid pro quo with some of the patent rules.

So almost anything that government does, you can find a way to make a connection to increasing domestic value added. Uh, and uh, so I think we’re gonna need, we’re gonna need something like that because. Uh, even if Mr. Trump changed his mind tomorrow morning about this whole tariff thing, uh, we’ve still got a situation where nobody can count on America being the biggest asset for an investment in Canada.

You know, we used to say, come to Canada, we’re next to America, and you can sell all your stuff there, and nobody believes that anymore. So, uh, we are gonna have to have, um, uh, I’d, I’d say a, a multidimensional industrial policy strategy to make sure that, uh, all of those, uh, value added industries in Canada.

Uh, are, uh, able to survive Trump, first of all, but even better, uh, than go on and grow. And we’ll, we’ll, we’ll end up, if we do this right, we’ll end up with a stronger, more self-sufficient economy.

Steve Paikin: Hmm. Jason, in our last couple of minutes here, it, it’s probably a good idea to steal ideas from other countries that would be doing things well that we wanna do well as well.

Um. What ideas do you see out there from other countries that we ought to rip off?

Jayson Myers: Well, I think, uh, particularly the European countries and Germany in particular, their focus on apprenticeships, their focus on young people. But you know, every country in the world is struggling right now with this revolution in manufacturing.

How do we, particularly small companies, how do we. Accelerate the adoption of technology and do it successfully. Because a lot of the, you can invest in it in a technology, uh, but it’s a, that’s a totally different question than can you manage that technology successfully? Can you actually generate value as a result of that?

So, you know, I think there are some very significant programs around labor force development. Maybe one of the things that we should be stealing is. A real focus on making stuff, a real focus on manufacturing or, and advanced manufacturing. Seeing that as a cornerstone of economic development. Have we gotten away from that?

Oh, I think we have, uh, I think it’s, uh, um, the last 20 years that, uh, we’ve moved away from manufacturing. We’ve put a, an huge emphasis on tech and we’ve got some of the best tech companies in the world, uh, here in, in Ontario. What we need to do is match those tech companies up with manufacturing customers and, and accelerate this adoption of Canadian made technology.

Uh, here in, uh, in Ontario. You know, there, there aren’t very many places in the world I. With this concentration of, uh, leading edge research of technology, large and small companies of startup ecosystems, as, uh, Michelle was saying of this, this great skills, uh, base in the colleges that provide that and, uh, and the variety of manufacturing, uh, that, uh, the Brendan was saying, how can, how can we.

Bring all of this together, drive more collaboration, make this, make this work, and actually create an economy in the future that, that really is leveraging up all of these great assets that, uh, that we’ve got. And one other thing, Steven, going back to this graph, I don’t believe for a minute that real GDP is a good measure of manufacturing activity.

You add more value in your product, you add more value in your service, and that. Discounts it as inflation. We are not measuring the impact of manufacturing in this country, uh, or the manufacturing supply value chain around, uh, around this really important sector.

Steve Paikin: Jim, in our last minute, I’m gonna ask you a question you’re not gonna like at all, but what, what the heck?

Let’s have a little fun here. Do you, are, are you prepared to give Donald Trump some credit in as much as he has really put the accent back on reshoring manufacturing to this continent and we’ve been getting away from it for the last many decades.

Jim Stanford: I, I don’t think so, Steve. I don’t give him credit because he is lying about it.

First of all, as Brendan pointed out earlier, they cannot quote unquote reshore all that stuff back to America. They don’t have the space, they don’t have the factories, they don’t have the capital, they don’t have the people to do it and mean most of it. They don’t want it. Most of the things that they’re talking about, uh, in terms of work, especially more labor intensive work, that’s.

Done elsewhere in the world. Uh, Americans, America as an economy doesn’t want that. They got 4% unemployment. They don’t, they are not in a depression, at least not yet. Uh, so this idea that they need to get everything back is wrong or that they can bring it back. Secondly, the idea that it was ever theirs to start with is false.

The jobs we have in manufacturing in Canada, we didn’t steal from America. We were manufacturing long before we ever had a a trade agreement or an auto pack. We made cars back in the. 19 hundreds. So they weren’t America’s jobs to take back. He is just playing for a domestic political audience and pushing these buttons about how America is supposedly mistreated.

And I’m the guy who’s gonna put America first. That reshoring narrative is not gonna work, and it’s not even what his motivation is. So this is where we have to, I think, have the confidence as a country to say, we don’t. We, well, you know, we are going to export to America, and this is important to us, but we have got the capacity to build a self-reliant, high value, productive, prosperous economy on our own, and, uh, reject trump’s false narrative here.

I.

Steve Paikin: Get off the fence and tell me what you really think. I’m Thanks

Jim Stanford: Steve. I’m gonna tell you what I really think about

Steve Paikin: this. Exactly, exactly. Uh, great discussion everybody. Thanks so much for coming on to TVO tonight. Thanks to Jason Myers from Next Generation Manufacturing in Canada. Brendan Sweeney from the Trillium Network, Michelle Rean, Conestoga College, Jim Stanford, who’s telling it like it is at the Center for Future Work on the left coast in Vancouver.

Thanks so much everybody. Have a grand day.

Jim Stanford: Thank you,

Steve Paikin: Steve.

Thank you.

Source: https://youtu.be/qNcojlYEdIU